Black people are poor relative to white people; nothing has changed in 70 years

The unrest in cities across the U.S. this week is just the latest manifestation of a struggle that will continue until the wealth gap between white people and black people is addressed, black economists said.

What is the wealth gap? It is the stark divide between how much capital white people and black people control.

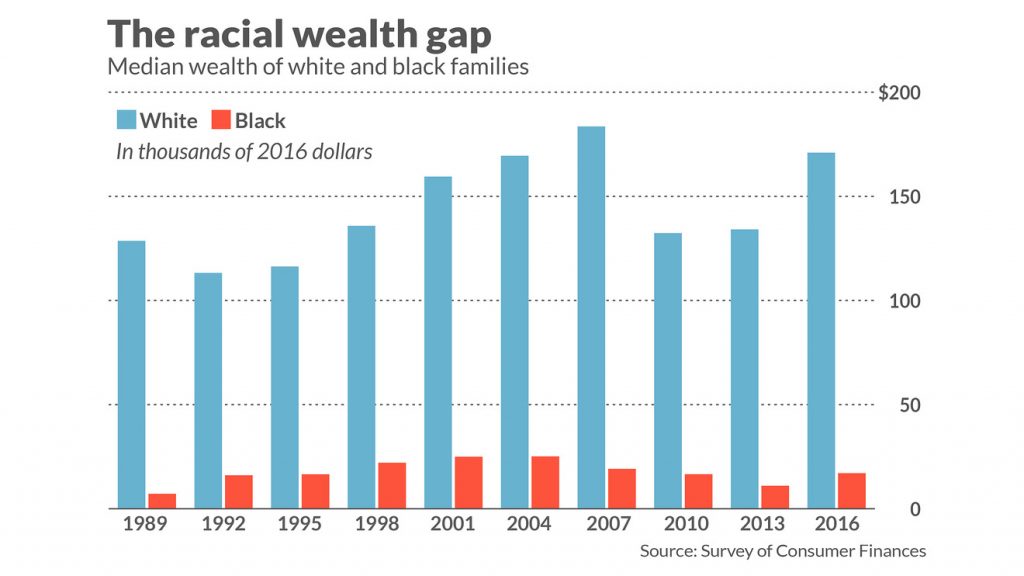

By one estimate, the typical white family has wealth of $171,000. This is nearly ten times greater than the $17,150 for an average black family.

Put another way, the typical black household remains poorer than 80% of white households.

This stunning wealth gap between the races has persisted, in good times and bad, for the past 70 years. It did not get better after the civil rights era legislation was passed in the 1960s or during the Obama administration.

And it will continue to fuel unrest, economists said.

“As long as we have racial wealth gap, we’re going to have a problems with race,” said Patrick Mason, an economics professor at Florida State University.

“The wealth gap is one of the reasons there are protests today,” said Linwood Tauheed, a professor of economics at The University of Missouri-Kansas City and the president of the National Economics Association.

“I don’t necessarily want to use the phase it was the straw that broke the camels back…but we have lots of evidence that this economic system is not benefitting the majority of the population,“ he said.

“African Americans are dissatisfied with the way things are — that’s not new for us— but now you find young college students dissatisfied with their future.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the fact that African-Americans have a lack of income to buy necessary health care, food and medicine and are suffering in greater numbers than white Americans.

Since the 1960s, the wealth gap has been largely ignored by the economics profession, black economists say.

For years, black economists struggled in the American Economics Association to even study the subject of wealth disparity between the races, black economists said. Universities and think tanks also didn’t support the work.

Black economists formed their own association, the National Economics Association, in 1969 to study the economic situation of black Americans.

“It was very difficult for a black economist to present a paper at an AEA conference that was questioning whether mainstream economists were understanding the economic disparity between the white and black community,” Tauheed said.

So called “mainstream” economists were really interested in more efficiency. “The wage gap is a question of equity or how to expand the pie,” said Karl Boulware, an economics professor at Wesleyan University. “The best way to think of wealth is to think of it as power,” he said.

In a statement to her membership Friday, former Federal Reserve chairman Janet Yellen, who is the president of the AEA, said her organization has “only begun to understand racism and its impact on our profession and our discipline.”

The causes

Black economists say one historical cause of the wage gap is slavery.

“I don’t want to offend anybody, and don’t want to be labeled a radical but the wealth gap has its roots in the starting of America,” said Samuel Myers, an economist at the University of Minnesota.

JIm Crow laws put in place shortly after the Civil War also kept black people impoverished.

A more recent and complex cause was the systemic exclusion of black people from the U.S. housing market beginning in the 1920. Housing is one of the main engines of accumulating wealth in America.

Restrictive covenants were put on houses that limited where black people could live, said Tauheed. These covenants, combined with discriminatory credit policies, kept black people from building wealth.

At the same time, government policies were put in place to assist whites to build wealth through housing.

For instance, in Minneapolis, where the current protests began after the death of George Floyd while being detained by police, white Americans first benefitted from the Homestead Act.

Then white soldiers coming home from World War II were given cheap loans to buy homes in the surrounding suburbs. These neighborhoods were off limits to black people, said Myers.

And the only prosperous black community in the city was razed to the ground to build a highway to St. Paul, he added.

“My feeling is until and unless white people acknowledge that their wealth holdings and therefore the wealth gap is attributable to unearned entitlements from public policy, then we’re not going to even have a conversation” about solutions to the wealth gap, Professor Myers said.

The solutions

Black economists think that reparations — the direct payment to descendents of former slaves — would narrow the wealth gap.

But they are under no illusion that this policy could be easily become law as blacks make up 12% of the population.

Reparations “run into conflict with the American mythology of how you get ahead, which says that it’s all individual effort,” said Professor Mason from Florida State.

Sen. Cory Booker, the black U.S. Senator from New Jersey, pushed for “baby bonds” during his brief run for the presidency last year. The accounts, presented at birth, would be seeded with $1,000 and receive up to $2,000 extra every year depending on family income. They could only be used once the child reached the age of 18, with the funds limited for paying college, a home, or to start a business.

This idea is race-neutral and poor whites would benefit the most from such a program, Professor Myers noted.

“I don’t really think in the final analysis baby bonds are going to dramatically narrow the wealth gap but I’d be really happy if I’m wrong,” Myers said.